Les auteurs ne travaillent pas, ne conseillent pas, ne possèdent pas de parts, ne reçoivent pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'ont déclaré aucune autre affiliation que leur organisme de recherche.

Edith Cowan University apporte un financement en tant que membre adhérent de The Conversation AU.

University of Plymouth apporte un financement en tant que membre adhérent de The Conversation UK.

Voir les partenaires de The Conversation France

Our insatiable demand for digital content and services has been driving a rise in energy-hungry data centres.

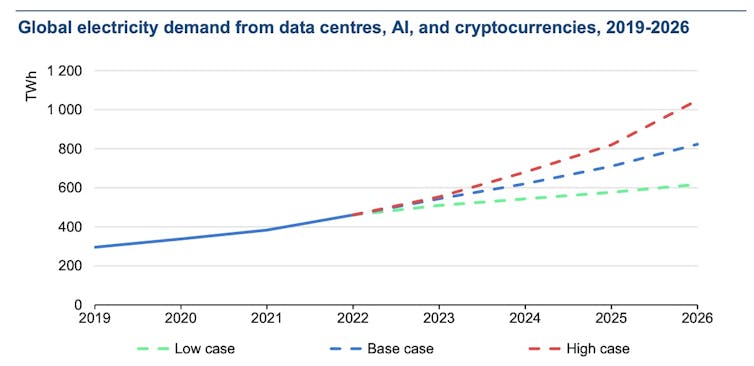

The International Energy Agency reports global data centre electricity consumption could double in a few short years, reaching 1,000 terawatt hours (TWh) by 2026. That’s roughly the same as generated by the whole of Japan per year.

Some predictions estimate 8–10% of the planet’s electricity production will be needed to sustain the relentless growth in data centres.

These figures are not uniformly distributed across the globe. In Ireland, where the sector is incentivised, data centres are predicted to exceed 30% of the country’s electricity demand within the next two years. Similar reports predict an increase in Australia from 5% to 8–15% of electricity by 2030.

So why do data centres need so much electricity, and is there anything we can do to make them more energy efficient?

Browsing the web, catching up on our social media feeds and binge-streaming the latest series are just some of the activities data centres support. In addition to these uses, power is also consumed at scale for artificial intelligence (AI) and cryptocurrency.

We may imagine data centres as rows of computers (servers) in racks with flashing lights, but, in terms of power usage, this is only part of the story.

When computers work hard, they tend to generate heat – lots of it. This heat is usually bad for the components within the computer or slows it down. With neither option desirable, data centres use extensive cooling systems to keep the systems running at a tolerable temperature.

Of the power consumed by an entire data centre, computers may use around 40%. A similar proportion is typically dedicated to simply keeping the computers cool. This can be highly inefficient and costly.

Where data centres are designed for liquid cooling – for example, by immersing the “hot” equipment in fluid, or cooling air directly – this can result in the waste of considerable volumes of water.

Aerial view of several white rectangular buildings surrounded by wind turbines and green fields." width="" />

Aerial view of several white rectangular buildings surrounded by wind turbines and green fields." width="" />

Using more renewable energy can decrease the demand on the electricity grid and the ultimate carbon footprint of a data centre. However, there are also many ways to reduce electricity usage in the first place.

Airflow: older data centres may still operate as a single large room (or multiple rooms) where the entire space is cooled. More modern designs make use of warm and cold zones, only cooling the specific equipment where heat production is a problem.

Energy recovery: rather than forcibly cooling air (or liquids) using electricity, the warm exhaust from data centres can be repurposed. This could replace or supplement water heating or central heating functions for the human-centric parts of the building, or even supply surrounding premises.

Aquifer cooling: in locations with convenient access to underground water sources, groundwater cooling is a viable option to disperse excess heat. One example can be found in Western Australia with a CSIRO Geothermal Project helping to cool the Pawsey data centre in Perth.

Optimisation: although there are no reliable figures to quantify this type of waste, inefficiently configured software or hardware can use up some of the computing power consumed at a data centre. Optimising these can help reduce power consumption.

Ironically, an increasing number of cooling approaches involve the use of AI or machine learning to monitor the system and produce an optimal solution, requiring additional computing power.

Optimising energy consumption, in general, can improve the costs of energy production. This idea opens a significant field of research on efficiently running all of the hardware in a data centre.

Physical location: by planning where a data centre is located, it is possible to significantly reduce cooling requirements. In northern Europe, the local climate can provide a natural cooling solution.

Similarly, recent trials using underwater data centres have proven not only effective in terms of cooling requirements, but also with the reliability of equipment.

The evolution of AI is currently having the biggest impact on data centre power consumption. Training AI platforms like ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, Copilot and others is having such an impact, organisations like Google have recently increased their greenhouse gas emissions, despite global efforts to invest in carbon-neutral initiatives.

Even once trained, the use of AI-enabled applications represents significant power usage. One estimate suggests AI searches use ten times the power of a more typical Google search.

Our desire to use AI-driven products (and the enthusiasm for vendors to develop them) shows no sign of slowing down. It is likely the predictions for data centre energy usage in the coming years are in fact conservative.

The lights are not going out just yet, but we are close to a tipping point where the power requirements of the systems we depend on will outstrip the generation capacity.

We must invest in clean energy production and effective energy-recovery solutions at data centres. And for now, perhaps we should consider if we really need ChatGPT to draw a silly picture.